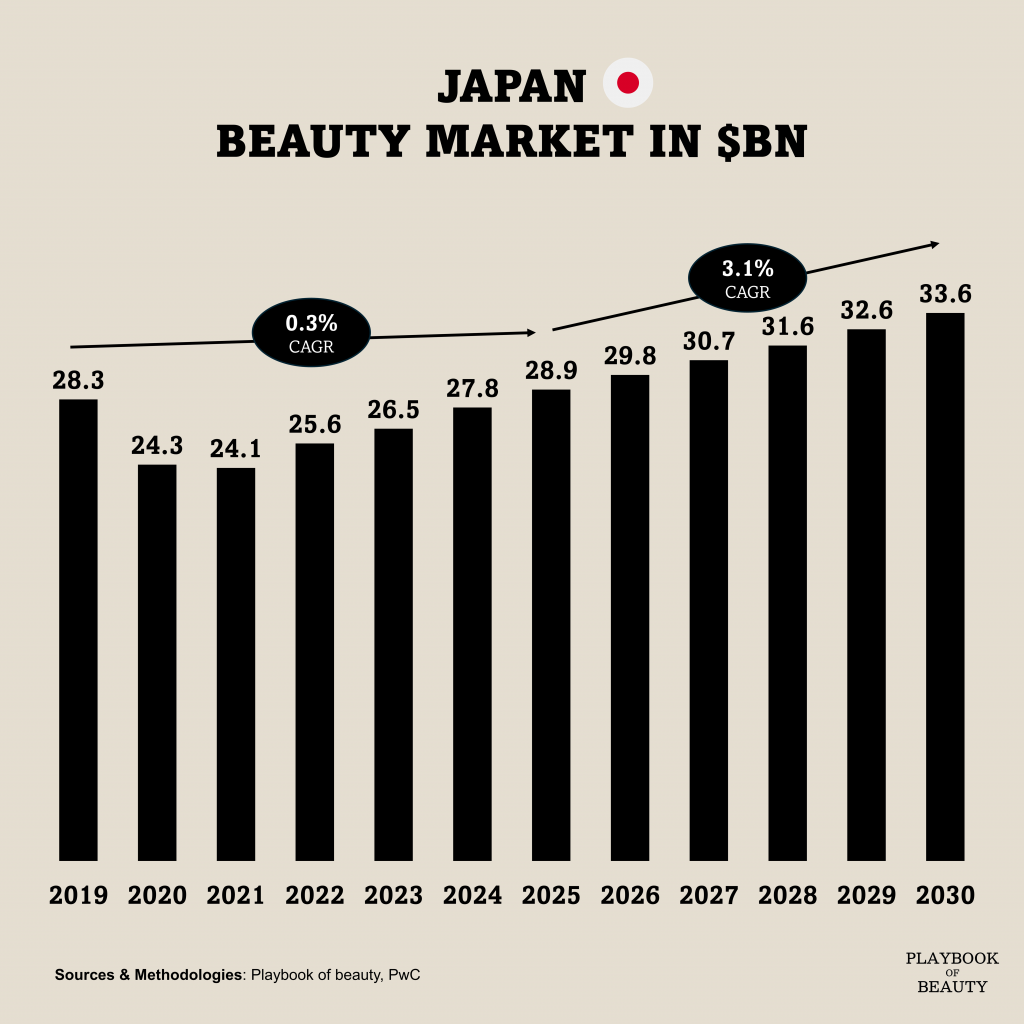

According to data from PwC, Japan’s cosmetics market, long the world’s third-largest, was overtaken by Brazil in 2023. Between 2019 and 2025, it stagnated posting a compound annual growth rate of 0.3% from 2019 to 2025 against a global growth rate of 5.3%. This is not a temporary slump but a reflection of deep-seated demographic and structural headwinds.

Growth is stifled by an ageing population with conservative consumption habits, which has entrenched the dominance of offline drugstores and stunted e-commerce penetration. The market has cleaved in two. Domestic giants like Shiseido and Kao have strategically retreated upmarket, focusing on luxury skincare for older, wealthier consumers. This shift comes as the purchasing power of Japan’s younger MZ generation remains constrained by the country’s prolonged economic stagnation.

Into this void have stepped foreign brands. Korea is now the leading cosmetics exporter to Japan, its colourful, trend-driven products dominating the budget-friendly colour cosmetics segment through potent soft power and digital savvy. Thai brands also hold notable share.

The paradox is strategic. While the current sales growth stems from high-margin, age-conscious products, the future consumer is being cultivated elsewhere. Japan’s OEM-heavy ecosystem struggles to foster innovative indie brands, leaving younger shoppers to seek overseas alternatives. The issue for international indie brand is that the entire market machinery, from distribution to marketing, is now optimised for luxury, not discovery.